This attitude survived Russia’s fleeting experience of modernity to become characteristic of the more-or-less closed society that embraced Russia’s elites. The great critic Iurii Lotman discerned in Russia what he called “an underlying binary logic of opposition [in which] individuals and groups conceptualize social life in terms of sets of absolute alternatives that admit of no compromise . . . either one or the other must be chosen.”1

Russians are also famous for their lack of moderation. “Sin greatly, that grace may abound,” describes a point of view that is an extravagant version of what St. Paul wrote long ago in his Epistle to the Romans (5:20) about the relationship between God’s mercy and men’s depravity; there is something very Russian about its suggestion of the powerful linkage of sin and grace. The idea that you should sin as little as possible so that there may be just enough grace for your needs sounds like some moderate, almost smug culture, far away from Russia. Something in the English-speaking world, perhaps.

A recent critic has echoed traditional voices in Russian cultural studies, proclaiming that Russia’s entire culture lacks “middle ground between the ideal of Sodom and the ideal of the Madonna.”2 What is needed, he goes on to suggest, is a concept of purgatory, something between the ideas of Heaven and Hell, with which the Russian story is so richly endowed. But both major and minor figures in Russian culture confront Heaven and Hell in rapid succession without even bothering to hypothesize about Purgatory, let alone thinking to stop off there.

Soviet Marxism was famously described as “dialectical,” and no doubt Marxist dialectics intensified the apparent clarity of the polarized contrasts.3 The precise meaning of this embattled term is not so clear, however. Does it not suggest that in Soviet or even Russian culture, distinctive and often extreme points of view bear within them to some unusual degree their semantic opposites? Are not dualisms and antinomies more common than in tamer cultures further West? To some, for example, it has seemed that the powerful self-assertion so often found in Russian culture coexists with its opposite: deep anxieties and fears of inadequacy, being wrong or not up to whatever the challenge might be. Impulses to desecrate and blaspheme coexist with the joy of self-lacerating repentance. The impulse to innovate radically coexists with a deep, if episodic desire to return to the “good old ways.” The coming of a radically secular regime to Russia in 1917 deprived God and Virtue of official representation for awhile, but it scarcely made Russia more moderate. In a broad sense, it was just as important — perhaps more so — to be in tune with History — meaning the Party — as it had been to be in tune with God and the Church. And the Party’s policies powerfully reinforced the strong polarity between friends and enemies.

Many of these extreme, contradictory and paradoxical impulses can be seen in the exhibition of Soviet Russian posters, caricatures and cartoons here assembled.4 The posters were directed first of all at a pre-literate or at least imperfectly literate audience, assumed to have been educated, if at all, by the village priest. The beautiful “ROSTA windows” in this exhibition represent the news-plus-propaganda impulse of the Communist Party in the early days of the Russian Revolution (image 1). Stenciled onto paper or plywood by teams of artists, they were sequenced like a comic book and issued abundantly in the very early 1920s.5 Generally hortatory and idealistic, they resorted only occasionally to satire, and of a kind that peasants could comprehend. But most of the cartoons and satirical drawings also on exhibit here were directed at a later and more sophisticated and urban audience, more caught up in the complexities of Russian culture, especially in attitudes toward the outsider enemy.

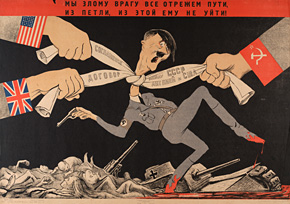

The posters and the various forms of visual/verbal assaults demonstrate a keen sense of hostile forces, often disguised or masquerading as friendly. The idea of secret enemies needing to be unmasked (image 2). was pervasive throughout the Soviet period but came to an unholy climax during Stalin’s cataclysmic purges. It should be said immediately, however, that the very real hostility of the outside world toward Bolshevism did little to allay the fears of the new Soviet elite and move them toward moderation. In the first days of the Soviet Union and even earlier, while the Civil War still raged, the targeted enemies were most often persons: the White generals (image 3) who struggled with the Red Army and the Bolsheviks over the political future, or foreign “bourgeois” nations that intervened from outside (image 4). But rich peasants (“kulaks”), international finance capitalists, or non-socialist “speculators” might also be fearsomely depicted (image 5). This was a more abstract and sociological enemies list than those of Imperial Russia.

The new Soviet regime was initially sympathetic to artists who were disposed to employ their talents anonymously and/or collectively. Like the artists who brilliantly but formulaically turned out the ROSTA prints, the three artists who called themselves the Kukryniksy developed a composite satirical vocabulary (image 6). Meeting at the state-sponsored Higher Artistic-Technical Studio (VKhUTEMAS) in Moscow in 1924, they were soon publishing their caricatures “under a joint signature.” The Grove Dictionary of Art has well characterized their style:

. . . an acute vision, a peculiarly grotesque three-dimensionality, a certain theatricality . . . , social awareness and. . .a sympathy with the traditions of nineteenth-century critical realism . . . .6

But many satirical artists maintained an individual identity, or sought to. Dmitri Moor, whose real name was Orlov (1883–1946) was one of the most notable. Born into a Cossack family, he had enjoyed a successful career as a satirist before 1917, but was of a left-wing point of view and readily cast his lot with the new regime; he taught at VKhUTEMAS between 1922 and 1930 (image 7). Bonnell describes him as the “unofficial ‘commissar of propagandistic revolutionary art.’”7 Viktor Deni (1893–1946), whose last name was shortened from Denisov, was a decade younger than Moor and from an impoverished gentry background; he was not initially as receptive to the Revolution. More of a satirical caricaturist than Moor, his posters were most popular and successful in the early days of the Revolution and experienced a reprise during the Second World War (image 8).8

The posters of the thirties were strikingly different from the more anarchic images that preceded them. The promulgation of socialist realism (1934) and the development of the full blown Stalin cult added to the monumentality and uniformity of the images. The principal contribution of Gustav Klutsis (1895–1944) was the introduction of photomontage into posters (image 9), an important innovation in the poster making of the thirties. The work of Ukrainian Viktor Koretsky (who was a full generation younger than Moor) had its principal impact during the Second World War and the Soviet “peace offensives” of the postwar period. The savage caricatures of Alexander Zhitomirsky (1907–1993), with their surrealist and pop-art imagery, both demonized and glamorized the Soviet Union’s Western enemies (image 10).9

It is certainly paradoxical that the great opponent of Russia during the Cold War should have been a culture with a few dramatic similarities to that of Russia but many more contrasts. If Russians hate compromise, Americans may seem to fetishize it, at least publicly. The culture of the United States of America, which has come to emblemize capitalism, must of course embrace deal-making, splitting the difference and making things work — quite unlike the Russians, whose culture is so uneasy about compromise, in olden times associated it with the devil.10

For Russians, the acquisitive individualism of the United States was the opposite of what was considered sacred under the old regime, or what was representative of good citizenship under the new. Publicly reviled as loathsome and hypocritical, it was often secretly envied by Russians, whose love of “stuff” had to be concealed, unlike the Americans, whose materialism was proof of God’s bounty and special concern for them. If the Americans built their “city on a hill,” it gradually became clear that it would not be an austere or uncomfortable place.

Some of the attacks on American racism or militarism — as seen in the caricatures and cartoons on display here — were largely intended by their creator to make successful careers in a world dominated by the Soviet version of Russian values. Many, however, may well have picked up a little steam along the way from Russian awe at the shamelessness of the Americans: building their “city on the hill,” while lynching “the Scottsboro boys” (image 11). (And those Americans don’t even know what hypocrites they are!)

The Americans, during the Cold War, were not disposed to take Soviet criticisms of American life very seriously. Few Americans wanted to risk being seen as pro-Communist or “fellow travelers.” If the Soviet critics charged Americans with racism, the accusation was less serious, because the source was so flawed: everybody knew that Soviet criticism was orchestrated by the Center and ebbed and flowed according to political needs and circumstances. So the nature of the critic actually mitigated the accusation; the Americans could focus on the Soviet critic’s lack of independence, rather than on the truth of what he was saying. Similarly, responding to Soviet criticisms of American “materialism” wasn’t too difficult for us. They’re just jealous of our success at creating affluence, it was commonly (and not entirely incorrectly) said by the Americans.

The rapidity with which friends and enemies could trade places also enhanced Western, particularly American, skepticism about Soviet criticism. Even the most bitter enemies could quickly become friends if circumstances seemed to dictate. In the aftermath of World War I, the British and Americans were portrayed as the most desperate and inevitable opponents of the Revolution, along with the White generals. But after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1939, the British and Americans became Soviet allies, and the Soviet division of the world into friends and enemies altered dramatically and rapidly (image 12). After the defeat of Hitler and the onset of the Cold War, however, the older friend-enemy dichotomy returned, but this time with an especially powerful focus on the United States, now the capital of all that was regressive and reactionary in the world. Both the Soviet Union and the United States expended a great deal of time and effort in describing the other as Hitlerian (image 13).

Racism presented a particular challenge to Americans defending their country against the accusations of Soviet critics. American racism couldn’t be straightforwardly denied; one response was to deny Soviet good faith or moral seriousness in making the charge, another was to claim that the Russian accusation was too sweeping or otherwise exaggerated. But one was constrained to admit there was something in it. Now that both the American society of the middle of the last century and the Soviet Union have slipped into the past, it may be easier to confront the Soviet charge more candidly (image 14).

Official America rallied against racism partly because oppression of blacks by whites made the U.S. look bad in the Cold War. Had African-Americans not actively protested the inaction of the American government, President Eisenhower might or might not have forced the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in September, 1957. But when Louis Armstrong — an unpolitical icon of American pop culture — denounced him as “gutless” and “heartless” it certainly helped propel him into action. The great trumpet player was about to take his band on a tour of the Soviet Union, but threatened to cancel if Eisenhower didn’t counter Governor Orval Faubus. The Russians also indicated smilingly that they would be very interested in Mr. Armstrong’s opinions on American racism.11 And Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard.

Inequality was a somewhat less difficult issue. If it was true that Soviet society had somewhat less economic inequality than the U.S. (and this was not always admitted), it was indubitably true that the political equality proclaimed by the Soviet leaders and those who spoke (and drew) for them was less than that of the bourgeois world. So the two sides engaged in a dialogue of the deaf: each trying to link the other with different kinds of inequality. Each side wanted to win a Cold War debate; there was little interest in the possibility that their opponents might be to some degree correct about them. The Cold War, in sum, was an inauspicious arena for honest self-criticism.

It certainly cannot be proclaimed that the various visions of the enemies of the Soviet world — these posters and especially the cartoons and satirical drawings — “hold a mirror up” to Western or American society in any straightforward way. Soviet and American cultural differences were enormous and no doubt propaganda was a good deal more focused and purposeful on the Soviet side. But especially in an age in which the worldwide image of the United States is at an all time low, it is interesting to confront these critical images from an earlier time, now emptied of any serious, practical challenge. Do we want to simply write them off as Communist propaganda? Or ought we to ask ourselves whether we can learn anything from contemplating such criticisms soberly?

— Abbott (Tom) Gleason,

— Keeney Professor of History Emeritus

1

See Tim McDaniel’s meditation on Lotman in The Agony of the Russian Idea, Princeton University Press, 1996, p. 17.

2

Mikhail Epstein, “The Demise of First Secularization: the Church of Gogol and the Church of Belinsky,” East European Thought, Vol. 58, p. 102. See also Iu. M. Lotman and B. A. Uspensky, “The Role of Dual Models in the Dynamics of Russian Culture”, in The Semiotics of Russian Culture, Michigan Slavic Contributions, Ann Arbor, 1984, pp. 3-35.

3

Victoria Bonnell, Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters Under Lenin and Stalin, California University Press, Berkeley, 1999, p. 187.

4

See the authoritative statement by Bonnell, “Bolshevik Demonology in Visual Propaganda,” Iconography of Power, pp. 187-224.

5

“ROSTA” stands for “Russian Telegraph Agency,” an agency later more or less replaced by TASS. For a good sample of the ROSTA posters, see Alex Ross, ed., Power to the People: Early Soviet Propaganda Posters in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Lund Humphries, (n.p.) Ashgate, n.d. (2008), pp. 18-21 and passim.

6

Art Encyclopedia, The Concise Grove Dictionary of Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002.

7

Bonnell, Iconography of Power, p. 11.

8

There are excellent biographical summaries of Moor’s and Deni’s careers in Stephen White, The Bolshevik Poster, Yale University Press, 1988, pp. 39-64.

9

Alexander Zhitomirsky, Robert Koch Gallery, San Francico, CA, 1994.

10

In the West, Iurii Lotman claims, negotiated agreement has lost its nefarious character, while in Russia it has not. Adhering to one’s agreed word can, even in the West, be a matter of the highest honor, but in Russia “service based on contract is bad service.” The unreserved “self-giving” is the model, in Russian culture, for personal relations of the highest type. Iu. M. Lotman, “‘Agreement’ and ‘Self-Giving’ as Archetypal Models of Culture,” in Lotman and Uspensky, Semiotics of Russian Culture, pp. 125-140, esp. p. 130.

11

See “Louis Armstrong, Barring Soviet Tour, Denounces Eisenhower and Governor Faubus,” (AP); David Margolick, “The Day Louis Armstrong Made Some Noise,” New York Times, September 23, 1957.